The seniors of Baruch College Campus High School are chipping away at college applications. Supplementals, financial aid, tours and personal essays are taking the forefront of many students’ minds. But there are other contributors to this process – the teachers writing our recommendation letters.

Last spring, the class of 2024, then juniors, rushed to request these letters. Counselors requested they ask one humanities and one STEM teacher, and students built up the courage to see if these educators do the honor.

Baruchians fill out a survey on Naviance to officially make the request. But after this happens, how do teachers go about writing the letters?

First, teachers need to consider the students they’re writing about. Earth science and AP Environmental Science teacher Ashley Grey makes a Google form with specific questions that helps her write the letters. It consists of questions such as: how did that student grow in her class, how do they describe themselves and why did they ask her to write their letter.

Grey appreciates how using a Google form gives the students a chance to reflect on their growth since sophomore year, as well as see how they characterize themselves and their future.

“I don’t think students have enough opportunities to reflect on that,” said Grey.

Chemistry teacher Ceren Kilic prefers to start with making note of the deadlines so she knows whose letters to prioritize. She says most of the letters were due Nov. 1 because of the growing popularity in early action applications.

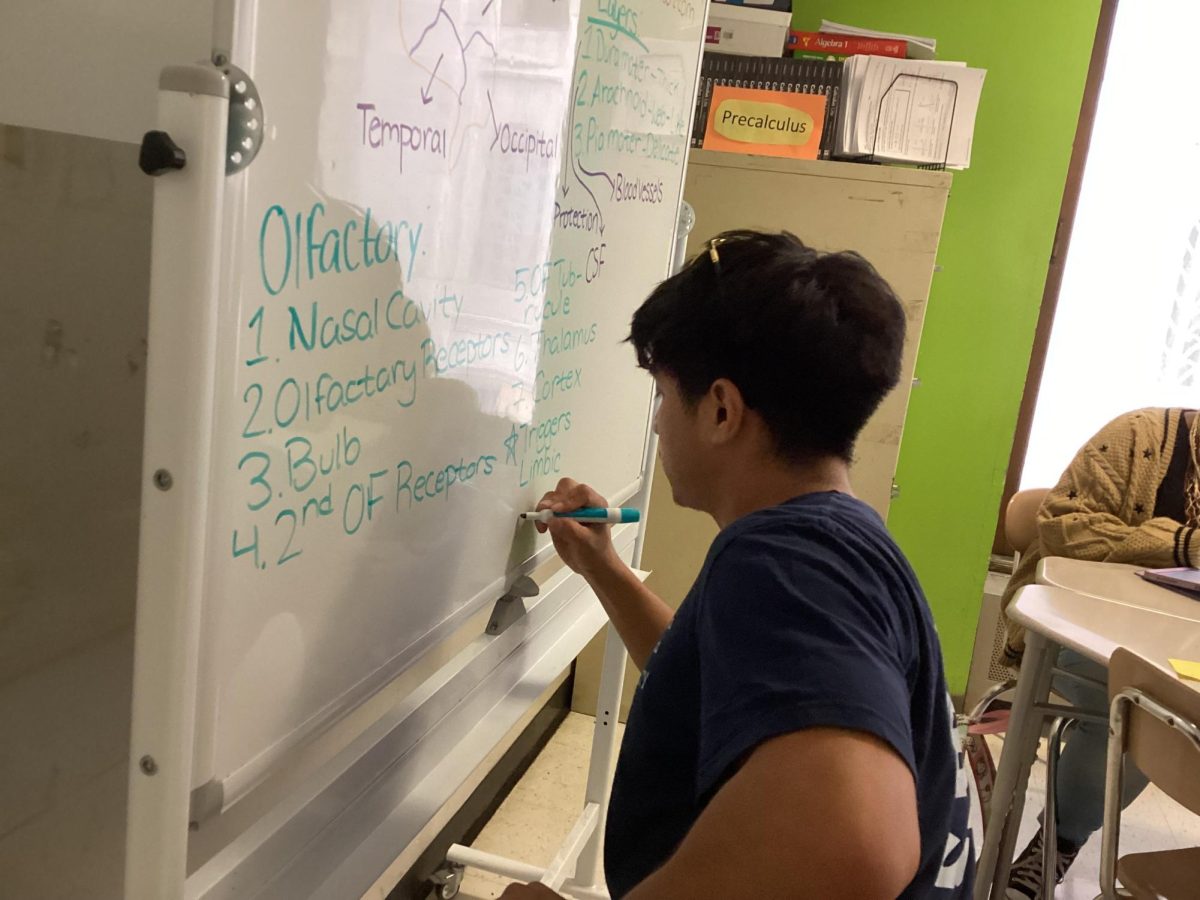

Calculus and AP Statistics teacher Laird Jonas also has his own first step. When he knows he has a letter to write, he spends the week reflecting on the student’s experience in his class, occasionally taking notes. He considers things like how the student would handle a difficult topic, if they are a “thinker” and how they work things through.

“I pretty much have [the letter] written – just not on the paper,” said Jonas.

These teachers then look at the required Naviance survey and then begin writing the load of letters.

This survey asks students questions about why they chose this teacher, how they describe themselves and their interests and how teachers may describe them.

“When I agreed to write their letters I already knew these are the students I would agree to write [for],” said Kilic, who had 37 letters to write. The students who Kilic accepted requests from were individuals who shined in her class and already having ideas for what to write about them made the load a little easier.

Jonas, who had 26 letters to write, shared a similar sentiment, saying some letters write themselves. Usually, though, more thinking is required. He likes to write about moments in his class where the student stood out.

“I like to talk about things that happened in class, things that students did – even outside of the academic realm,” said Jonas. He often brings up instances like a student helping someone who was absent and didn’t get the notes, or a student having – as he calls it – a “math moment.”

Grey, with 18 letters to write, likes to follow a certain structure with her letters. She writes paragraphs describing the student’s growth in her class, how they present as a science student and other interesting facts.

“I like to highlight very unique details about the student,” said Grey.

One possible challenge is when the letter is for a student the teacher hasn’t taught in a while. This is especially prevalent for Grey, who teaches a sophomore-year class.

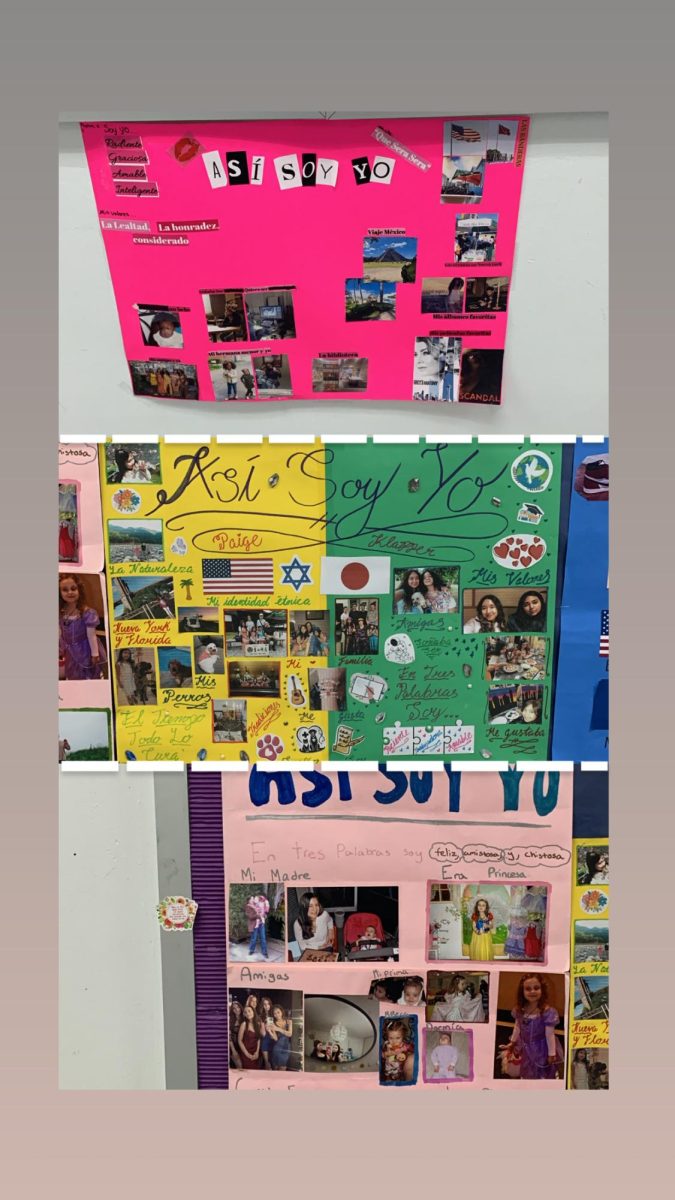

However, Grey has found those who ask her to write a letter are students who worked to maintain some form of relationship with her – whether that be them stopping by to say hello or participating in a club she advises, such as the Lorax club and Asian Affinity Club.

If she hasn’t interacted with the student in a while, she tries to see them at least once before writing the letter and maybe ask the student’s current teachers about how they are in class.

Grey feels it’s important to see the students at least once as seniors because she knows they were likely less mature as sophomores and personal growth is something she would want to note.

Kilic doesn’t find it difficult to remember students asking her for letters since she taught them just a few months ago as juniors.

“I feel like I have a clear picture of these students and how these students were in my classroom. I don’t think I’ve ever struggled writing a recommendation letter thinking, like: ‘How was this student in my class? I totally forgot who they were’,” said Kilic. “If they were leaders in my classroom, I just know what to write about. I do pay a lot of attention to that – leadership, facilitation…”

Some teachers find the most difficult part of the recommendation letter process is deadlines. They all wish to be diligent with these letters, as they hold a lot of weight, but it can be hard to find the time with other things on their plate.

“I really wanna spend time, say what the colleges should hear about the students,” said Jonas. He also said he doesn’t want these letters to ever feel like a part of a checklist he just wants to get over with. It is not busy work for him, and neither is it for Grey.

“This letter has a lot of weight for the student so I don’t wanna just be like ‘I’m gonna just get this off my list’,” said Grey.

For Kilic, each letter takes a “good 45 minutes.” Grey and Jonas take about an hour per letter. Since Kilic is the only science teacher for juniors (as opposed to every other core class which had an AP and honors class), she has much to write.

“But, you know, there’s nothing to dislike about it, it’s just the process – everyone needs to write recommendation articles for college,” said Kilic.

Even if it’s a lot of work, teachers don’t seem to see the task as a burden. In fact, they find joy in it.

“I see it as my duty; I see it as something I have to do for my students so that they can have bright futures,” Kilic said.

Letters of recommendation are a chance to say something about a student that cannot be expressed numerically, and that’s part of why teachers find them so important.

“I think it’s an opportunity to talk about things that the students do as a learner or the way students show that they are learners that will not show up on the transcript,” said Jonas. “What can I say that will set this 95 apart from other ninety-fives?”