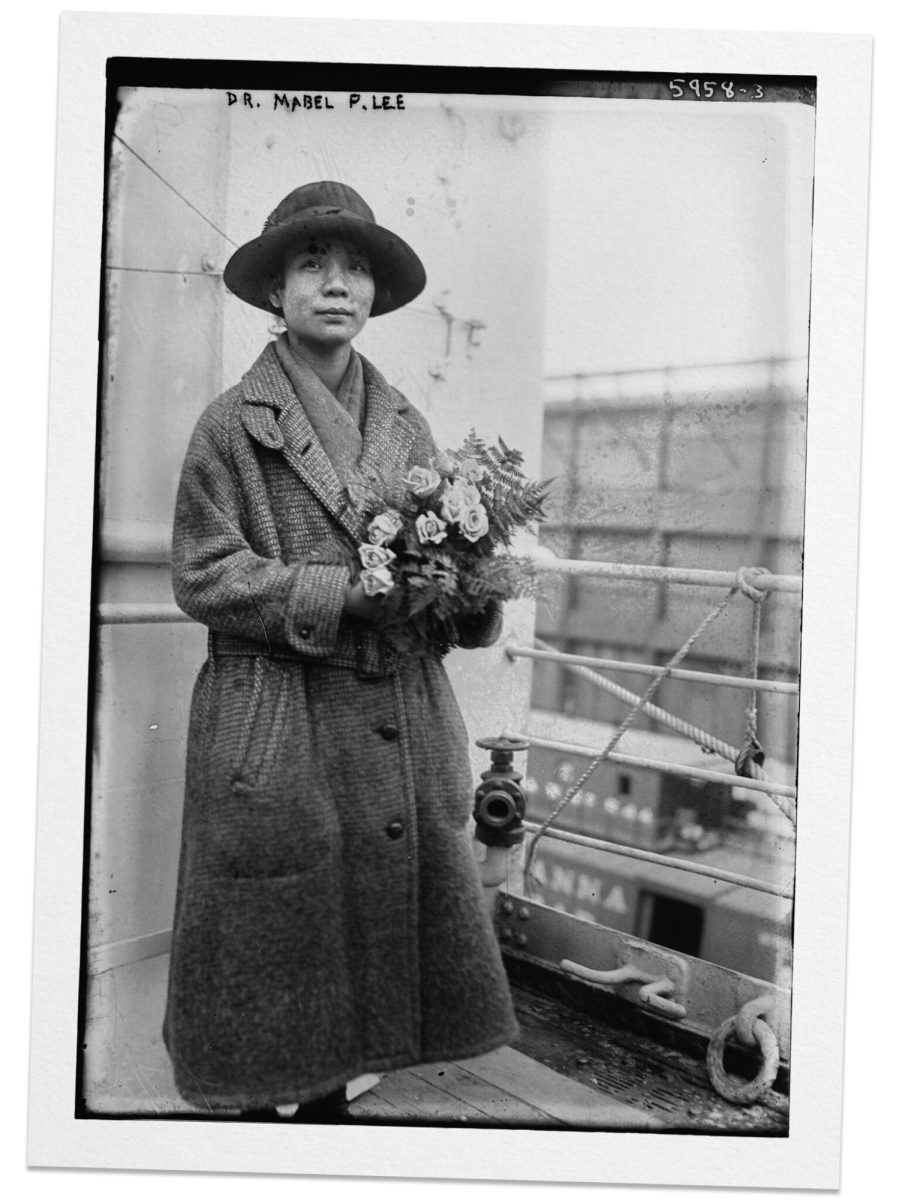

How did a 16-year-old Chinese immigrant lead a women’s suffrage parade in New York City? Despite having limited rights due to the Chinese Exclusion Act, Mabel Ping-Hua Lee devoted most of her life advocating for women’s rights, equal educational opportunities and helping her peers in Chinatown. Although she is not well known, her contributions to the women’s suffrage movement made a significant impact in New York City.

In 1896, Mabel Lee was born in Guangzhou, China. When her family moved to New York City, her father— Lee Too—became involved with the first Baptist Church in Chinatown. Her father was a Christian missionary which allowed them to immigrate to the United States—one of the few exceptions to the Chinese Exclusion Act. This legislation banned Chinese immigrants from coming to the U.S. and becoming U.S. citizens; however, this did not prevent Lee from becoming an advocate in her community.

Even from a young age, Lee had a heart of gold and was outspoken with her opinions. She helped fundraise for Chinese communities that were impacted by famine for the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) and attended meetings by many suffrage groups like the Women’s Political Union. For this reason, the suffragists asked Lee to lead a suffrage parade—she was 16 years old at the time.

On May 4, 1912, over 10,000 participants rode on horses along 5th Avenue, protesting from Greenwich Village to Carnegie Hall. The New York Times named her, “the symbol of the new era when all women will be free and unhampered.”

When she was 16, Lee enrolled in Barnard College where she continued to fight for women’s rights by writing for the college’s newspaper, The Chinese Student Monthly. She wrote against women being forced to choose between having a career or having a family and believed that it was possible for women to have both simultaneously.

At a Women’s Political Union’s suffrage meeting, she delivered her speech China’s Submerged Half where she voiced her convictions about the idea that all children should have the same learning opportunities regardless of their race or gender. In her address, she stated, “They have received so little education if any at all (…) despite these limitations, the Chinese women of the future who with unbound feet and untrammeled minds, will face a new dazzling era.”

Part of her motivation was to take what she learned from the women’s suffrage movement in America to advocate for women’s rights in China. Lee’s dream of opening an all girl’s school stemmed from her mother’s inability to receive an education.

In 1917, the orator attended another suffrage parade. Later that year, white women were granted the right to vote in New York.

After graduating from Barnard, Mabel Lee attended Columbia Teachers College and became the first Chinese woman to receive a Ph.D. in economics in the U.S.—a significant accomplishment because at the time, Columbia only accepted a limited number of women to their graduate school.

Even with all her studies, she still found time to support the feminist movement. Mabel Lee spoke with multiple suffrage groups where they included her, but excluded Black women. For instance, the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was led by suffragist Carrie Chapman Catt who rejected Black women from joining the group because she believed that was the only way to appeal to Southern legislators. During this time, suffragists like Catt prioritized the rights of white women. Meanwhile, most of them welcomed Lee by asking her to deliver speeches and lead marches.

However, not everyone accepted Mabel Lee and her activism. As a suffragette, she faced sexism, and as a Chinese woman, she faced racism from the Chinese Exclusion Act. Articles that praised her were often tinged with backhanded compliments that perpetuate harmful stereotypes about Chinese women. One newspaper article called her, “a hopeless little suffragette” of the “Chop Suey District.” Nonetheless, the women’s suffrage movement was successful, and the 19th Amendment was passed in 1920, granting white women the right to vote.

It wasn’t until the Voting Rights Act in 1965 that all women could vote regardless of their race. After this accomplishment, Mabel Lee’s plan was to move back to China to start a girl’s school and advocate for equal educational opportunities like she’d always dreamed of. However, when her father passed away in 1924, she went back to the U.S. to take care of her mother and take over her father’s ministry at Morningside Mission.

Subsequently, Lee became the minister of the first Chinese Baptist Church. The Baptist Mission Society wanted to sell the property, but refused to sell it and cede power to Mabel Lee because she was “unordained” and a Chinese woman. Ultimately, she wanted the property to belong to the church, but it wasn’t until one of the members of the Baptist Mission Society passed away in 1944 that she was able to acquire the title for this property.

Furthermore, Lee established the Chinese Christian Center to pay tribute to her father’s legacy. The community center provided services such as a kindergarten, free healthcare, English language classes and free job training.

Overall, Mabel Ping-hua Lee is an inspiring figure because she worked hard to promote women’s suffrage in the U.S. even though the outcome did not benefit her until years later. In fact, there is no evidence that suggests that she ever participated in a U.S. election or became an American citizen when the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in 1943.

Mabel Lee’s legacy is still around today. When voters are casting their ballots, they can remember one of the activists who fought for women’s suffrage. On July 24th, 2018, by an act of Congress, the post office on Doyer Street in NYC’s Chinatown was renamed in her honor.