Why I Hate #BookTok

October 30, 2022

We often picture reading as a solitary act. It’s something one does in bed or at the beach, where they can sit by themselves as they soak the words up. But reading a text is only half the act – what comes after is discussion.

After finishing a book, it’s a basic impulse to talk about it. You want to let people know what carved itself in your mind the moment you read it on the page. You want to share this story with others. In order to satisfy this insatiable need to discuss the latest book you’ve read, spaces on the internet have emerged – one of them being #BookTok.

If you’re wondering what #BookTok is, here’s a simple definition: it’s a hashtag on TikTok that prompts the app’s algorithm to group videos on book-related topics together. Once you click one #BookTok video you will see five more. If you like five TikToks about books, congratulations, you’ve officially been inducted into #BookTok. While this seems like the perfect equation for an avid reader, there are a few problems with #BookTok, ones that only reveal themselves the deeper you dive.

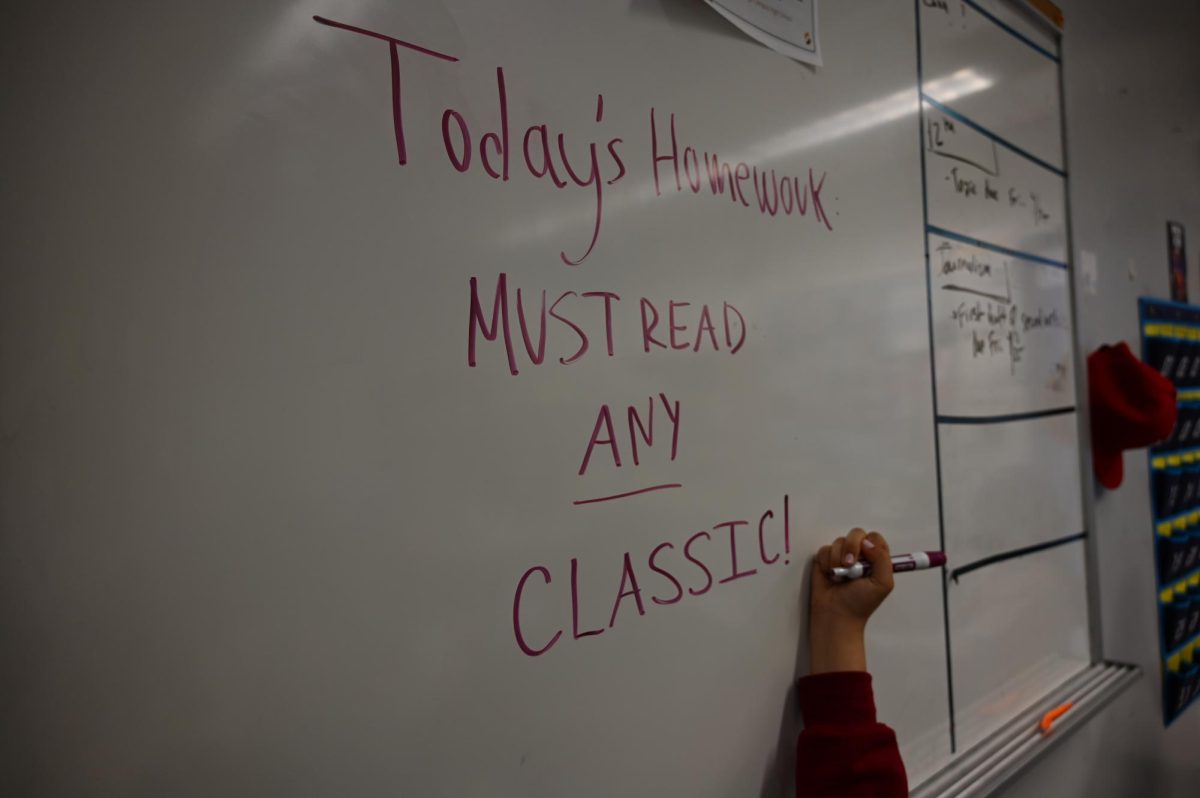

First: The same books get talked about over and over. If you take a trip to Barnes and Noble, you’ll see a table blanketed by TikTok books – that’s how ubiquitous they’ve become. On #BookTok, you don’t hear about those weird, genre-bending and perspective-changing books that an acquaintance might recommend. Instead, you hear the names Sally Rooney, Colleen Hoover, and Taylor Jenkins Reid ten million times. Majority of these popular titles are written by white authors and have romance as a focal point of the story. Speaking of…

Second: Everything comes back to romance. Users fail to accurately describe the books they’re recommending, choosing to define books by tropes they utilize rather than actual content. Holly Black’s The Folk of the Air trilogy gets a lot of traction on TikTok for its “enemies to lovers” romance – likely the most recommended trope on the app. Many have complained that this description fails to describe a plot that largely circles around monarchical politics with romance as a side plot. This is yet another way #BookTok becomes like the algorithm that serves it: repetition that leaves the more diverse and non-romantic stories on the outskirts.

Third: Quality is equivalent to how much it makes a user cry. A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara has done numbers on #BookTok. It centers on the pain and suffering four boys endure throughout their life. Booktriggerwarnings.com lists 25 major (and appalling) content warnings for this one book, which paints an ugly picture of the plot. And though I’ve never read it, I’ve heard enough to know that I never will. Yanagihara did no research into the immensely traumatic experiences she was explicitly portraying – a decision which has been criticized by experts. It sent one of my favorite YouTubers, A Clockwork Reader, into a depressive episode. Of the book, she says, “I don’t think it should have been written…I think it’s cruel and demeaning to anybody who has experienced any of the traumas that are in the book…I just think it’s sick.”

Another YouTuber, Man Carrying Thing, said, “[A Little Life] becomes problematic when you read the author’s words about the book…There is this kind of malicious intent by an author to say that ‘sometimes, you need to give up, and in the most extreme way. You need to die.’” He goes on to quote Yanagihara, who basically explains that she wrote the book to prove that she doesn’t believe “life is always the answer” to suffering. This idea can promote dangerous behaviors and is wildly harmful, especially to thirteen-year-olds who aren’t expecting to be emotionally damaged by a TikTok recommendation. But the book remains popular because what determines quality if not the harm you endure?

Fourth: There is not enough time for nuance. The last book I read was Stephen King’s It, and while I greatly enjoyed it, my list of grievances is just as long – if not longer – than my list of reasons why I liked it. Every time I bring It up to a friend, I supply ten reasons why they shouldn’t pick up the book. On #BookTok, that doesn’t exist. There’s no room to think critically about a text. Instead, you must definitively prove if it’s flawless or a problematic piece of garbage that should burn Fahrenheit 451 style.

Reading on #BookTok is not about engaging with a complicated text and hoping to learn something from it – it’s about the trend. Users seem to be making books about romance and trauma into marketable aesthetics, and the conversation quickly turns from “this book is about x, y, z and I have thoughts” to words indecipherable by anyone who isn’t caught up. Discussing a text is no longer a way to bridge the gap – it’s a form of exclusion.